About Us

Welcome To Garnsey Bros. Rentals

Where it all begins...

The onset of World War II saw the need for increased protection of Portsmouth Harbor that could not be met by any of the other existing forts of the area. Fort Foster only had room for one new battery, but there was no space available at any of the other forts without destroying existing batteries, which was deemed unacceptable. The Coast Artillery had decided that the better solution to condemn and purchase all of the land between Odiorne’s Point and Frost Point in Rye, NH to become Fort Dearborn. Two batteries of modern twin 6-inch guns (standard 200-series) with a range of 15 miles, and a single battery of twin 16-inch guns (100-series) having a range of 25 miles, were planned as part of the new defenses.

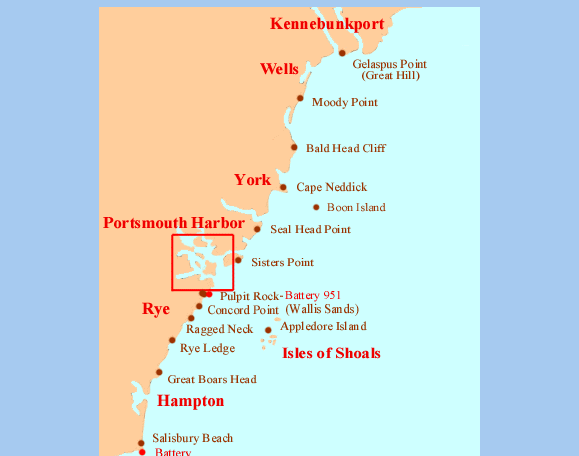

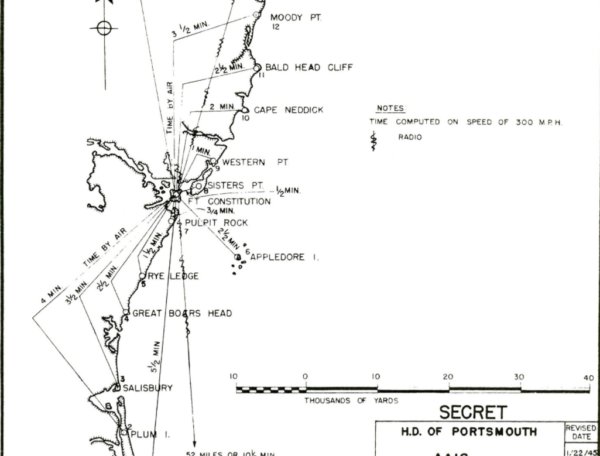

In late 1942 construction was begun on fourteen Fire-control Stations (or Base-end Stations) that were needed for the new gun batteries. These ranged between 25 miles north and 25 miles south of Frost Point, the maximum range for the 16-inch guns of Battery Seaman. Five of those concrete towers still exist today (as of 2008), located at Moody Point, Pulpit Rock, Great Boars Head, Appledore Island, and Halibut Point.

With its original purpose to identify unwelcome intruders and to call in their coordinates to a central plotting station at Fort Dearborn…the concrete “lookout” tower was erected in September 1943 as a Base-End Station to support US Battery 103/Seaman (B13 S13) at Fort Dearborn in Rye, NH. The roof deck was used for anti-aircraft intelligence service (AAIS OP 12) and Searchlight Position #20 was located nearby just east of the tower. The attached “house” (Garnsey Bros Rental office) as it stands today is not original to the WWII period although a 2-1/2 story wooden cottage was attached to the tower and was identical in design to the stations at Bald Head Cliff and Salisbury Beach.

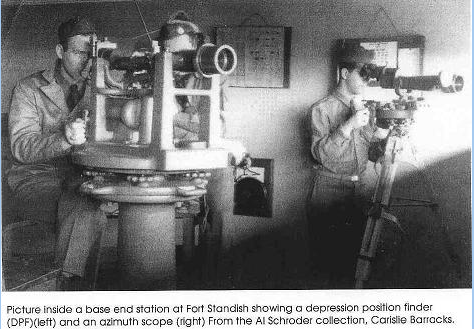

Despite popular myths, the base-end station towers were not submarine lookout towers. They were aiming and tracking stations for the long-range artillery against enemy surface ships. They also served as advance warning stations against enemy aircraft in many locations. Once an enemy surface ship was spotted by a Navy or Coast Guard vessel or aircraft far out at sea, the Coast Artillery then tracked these ships with continuous sightings made with the optical instruments at Base-End Stations, coordinated by time-interval bells that rang synchronously (every 15 or 30 seconds) throughout the entire system. A Depression Position Finder (DPF) scope was used to spot and track the desired target, and a smaller azimuth scope was used to report and correct shell hits and/or misses. Using this method, the location of a target could be determined from several towers at the same instant. Data from these observers, along with weather and tidal information, was telephoned on secure lines to bomb-proof plotting rooms. A primitive computer, which had replaced the earlier manual plotting boards, processed all of the incoming information and then provided artillery crews with aiming coordinates based on the predicted location of the moving enemy ship at the time of firing. Because the shells might be fired as far as 25 miles (for 16-inch guns), the rotation of the Earth also had to be taken into consideration when calculations were being made.

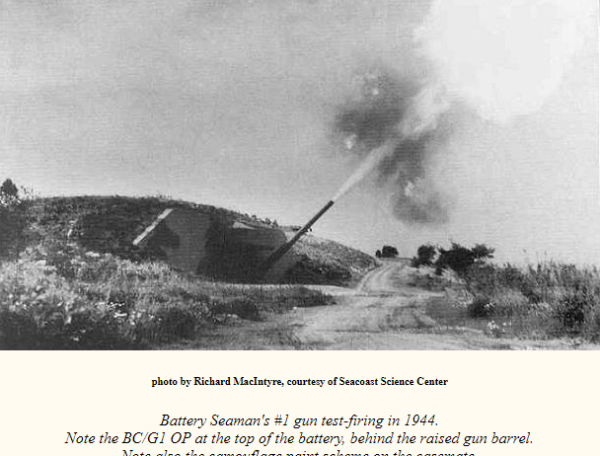

Each observation level in a station was used exclusively for one specific gun battery or command post, usually manned by six observers per level, and three observers for each AAIS post. Each station had a barracks, either attached or unattached to the tower itself, and was usually made to camouflage the structure (if attached) as a beach house or church or other such structure. The searchlight stations were manned by eight men per light, and usually shared the same barracks with the observation crews. Most of the base-end stations were not manned during the later years of the war, as the threat of enemy invasion ceased to exist, and also because the new invention of radar had made the towers obsolete as tracking stations. Some were kept in service, however, to serve as a backup to the radar. Fort Dearborn’s two 16-inch guns were “mothballed” immediately after test-firing in 1944, therefore the stations assigned to these guns were actively manned only once in order to test the equipment.

Since 1965 the Garnsey Brothers converted the concrete tower to a lighthouse and built the attached house/office to welcome vacationers to the area.

Garnsey Bros Rentals has proudly served Ogunquit, Moody and Wells Maine property owners and their guests for over 50 years.